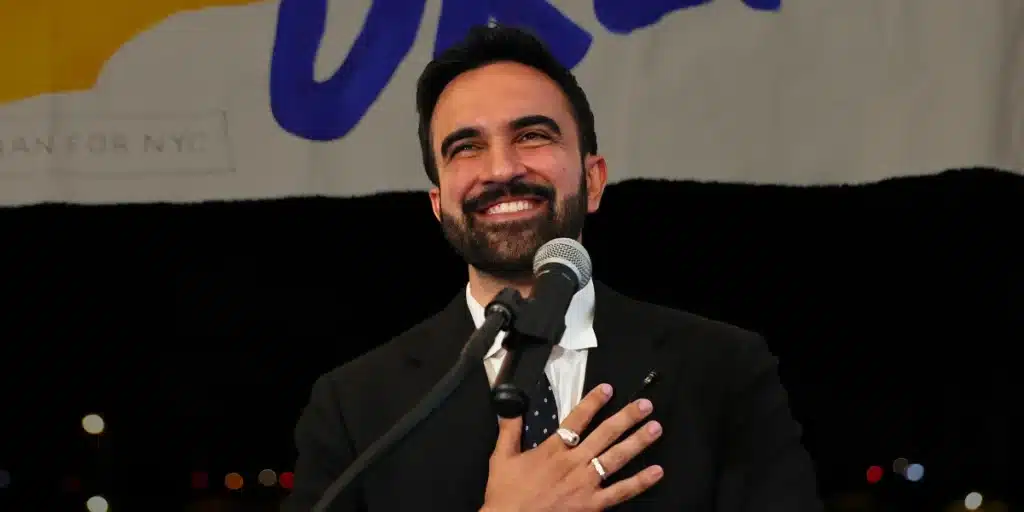

New York’s newest mayor didn’t arrive alone. As cheers swelled for 34-year-old Zohran Mamdani, cameras kept finding the woman at his side—Brooklyn illustrator and animator Rama Duwaji—whose quiet presence and careful privacy have become part of the city’s biggest story.

They met the way many modern romances do: a Hinge match in 2021. He had just entered the State Assembly; she was building a freelance career, sketchbook in hand, navigating post-college gigs across New York. Coffee led to long walks, neighborhoods folded into conversation, and in early 2025 they slipped into the City Clerk’s office and made it official—no spectacle, just vows and a subway ride home. Months later, when online attacks tried to turn her into a campaign talking point, he answered with a line that has since followed them into City Hall:

“Three months ago, I married the love of my life, Rama, at the City Clerk’s office. Now, right-wing trolls are trying to make this race—which should be about you—about her. Rama isn’t just my wife; she’s an incredible artist who deserves to be known on her own terms.”

If the spotlight has been bright, her instinct has been to soften it. After the primary, she declined interviews, telling friends the sudden attention felt overwhelming. Yet those who know her work already understood the magnetism. Born in the U.S. and raised in Dubai from age nine, she often describes the tug of a layered identity—Syrian and American, Arab and Western—threads that run through her images of sisterhood, kitchens, balconies, and borderless conversation.

“I was born in the States and lived here till I was nine,”

she once explained on a podcast, admitting that before the war in Syria she sometimes dodged that part of herself. Art changed the calculus: the more she drew, the more she spoke.

“I believe everyone has a responsibility to speak out against injustice, and art has such an ability to spread it.”

From a small studio in Brooklyn, she’s assembled an unusually broad portfolio—commissions and features with The New Yorker, The Washington Post, BBC, Apple, Spotify, VICE, Tate Modern. In workshops for the London publisher It’s Nice That, she coached younger artists through visual storytelling; on quieter days, she steps away from the screen to hand-paint blue-and-white ceramics, carrying her linework from tablet to glaze. In 2024 she completed an MFA in Illustration as a Visual Essay at the School of Visual Arts.

Her thesis, “Sahtain!”—Arabic for “bon appétit”—turned recipes into memory maps: cooking as inheritance, flavor as family. The program’s chair, Riccardo Vecchio, called her “very focused on her work,” noting how deliberately she centers perspectives too often trimmed out of Western art.

The public has taken notice for reasons beyond résumés. Election night turned social feeds into a chorus. One post crowed, “Rama is giving First Lady!!! So poised!” Another, more blunt: “That face card is lethal.” A third tried to square the aesthetics with the ethics: “It really shows how being a kind, friendly man gets you a beautiful, artistic wife.” Even hyperbole—“modern-day Princess Diana”—cropped up between reposts of her illustrations. She didn’t answer any of it; the work has always been her reply.

Alongside her, Mamdani’s biography traces a different arc that meets hers at purpose: born in Kampala, raised in Cape Town, moved to Queens at seven; Bronx Science, Bowdoin, then a job as a foreclosure-prevention housing counselor that sharpened his politics into a simple provocation—that markets shouldn’t decide dignity. He broke ground in the Assembly as one of its youngest members and only the third Muslim ever elected there. On election night, he thanked the city for choosing an immigrant to lead it; the subtext was standing beside him.

With the move to Gracie Mansion, New York gains a first lady who is both Gen Z and gently contrarian about the role. No staged speeches. No churn of glossy profiles. Just a creative practice that already reaches hundreds of thousands online and classrooms full of young artists offline. Whether she continues to orbit the frame or steps closer to it, she’s already reshaping the silhouette of public partnership—art forward, empathy first, and privacy defended without apology.

The fascination, then, isn’t only that she is married to the mayor. It’s that her story mirrors his: two children of elsewhere who chose this city, two lives built on work that tells people they’re seen. He will spend the next years arguing policy—rent, buses, childcare, housing—inside a building on the East River. She will keep drawing kitchens and courtyards and women in conversation, insisting that belonging is a daily verb. Between them is a simple compact: you lead; I’ll keep making. And, when needed, they’ll switch.

For now, the frame holds steady: a new mayor stepping into the light, and beside him the artist who prefers to draw it—quiet, resolute, and very much her own.