More than half a century after it first aired.

Gilligan’s Island continues to enchant viewers of all ages with its bright tropical setting, its unforgettable ensemble of castaways, and its blend of slapstick humor and charming absurdity.

Although the sitcom ran for only three seasons from 1964 to 1967, it quickly cemented itself as a cornerstone of television history — in large part because of endless reruns that introduced new generations to the misadventures of seven unlikely survivors stranded on a desert island.

Yet part of what makes the show endlessly fascinating isn’t just the escapades on screen but the stories, bloopers, and quirky production realities that emerged behind the scenes.

Far from diminishing its magic, these details have become part of the show’s enduring appeal.

At its core, Gilligan’s Island tells the simple, repetitive, and infinitely meme‑worthy tale of a boat trip gone horribly wrong.

What was only supposed to be a “three‑hour tour” turned into a lifetime of comic misfortune when a storm stranded a diverse group of passengers on an uncharted tropical isle.

The passengers included the well‑meaning but hapless first mate Gilligan; the gruff but lovable Skipper; millionaire Thurston Howell III and his refined wife Lovey;

movie star Ginger Grant; wholesome farm girl Mary Ann Summers; and the brainy, resourceful Professor Roy Hinkley.

Together, they provided endless opportunities for misunderstanding, invention, and laughter — but what most casual viewers didn’t realize at first was that the show itself came with its own list of imperfections that became part of the fun.

One of the most famous goofs, and perhaps the most beloved among old‑school fans, occurs right in the opening credits of the show.

As the passengers board the ill‑fated S.S. Minnow at the start of the voyage, careful viewers have pointed out that the number of figures on the deck doesn’t always match the story’s setup.

In a few wide shots, more than the seven main characters appear aboard the boat — apparently because stand‑ins were used for some distant shots when the real cast wasn’t available.

This small continuity slip has delighted eagle‑eyed fans for decades, becoming one of those classic television curiosities that doesn’t harm the charm of the series but gives viewers something extra to notice.

Beyond this early intro quirk, other goofs crop up across the episodes.

In the season two opening credits at the lagoon set, for example, the S.S. Minnow looks noticeably different from earlier depictions, and even its beach placement shifts inexplicably from one scene to the next — a continuity oddity that makes it seem as if the castaways occasionally moved their rescue‑hopes boat around like misplaced furniture on the set.

And then there are the blunders that crop up during actual episodes. In one, castaways Ginger and Mary Ann smell fudge burning in their hut and rush in to investigate — only for the structure to collapse and reveal an empty interior.

In another, the Professor’s ingenious attempt to glue the Minnow’s broken hull back together results in collapse, yet the boat inexplicably reappears intact in a later installment.

Even wardrobe continuity was loose: Mary Ann, Ginger, and the Howells appear in multiple outfits throughout episodes despite having supposedly been stranded since the ill‑fated departure, and at times Gilligan himself is seen wearing actor Bob Denver’s real wedding ring.

These sorts of goofs might frustrate a modern binge‑watcher with a pause button and slow‑motion replay, but for generations of fans they became part of the fun.

Spotting continuity quirks and small mistakes evolved into a shared pastime, adding extra layers to the show’s rewatchability.

Instead of diminishing the magic, the imperfections help remind audiences that this was filmed with a modest budget, tight shooting schedules, and a lot of creative improvisation.

Many fans say that discovering these oddities turns viewing into a kind of participatory experience — searching for hidden equipment in the background, noticing props disappear between cuts, or realizing that the “deserted island” occasionally shows glimpses of modern buildings in the distance because of the soundstage location.

Part of the reason for these quirks stems from the realities of where and how the show was filmed.

After the pilot was shot on location in Hawaii in November 1963, the bulk of the series was produced at CBS Studio Center in Studio City, Los Angeles.

There, a backlot lagoon was purpose‑built to simulate the tropical paradise of the castaways, but the water was only about four feet deep, often brackish, and frequently needed refreshing.

The lagoon sat just a few hundred yards from the 101 Freeway, so production crews sometimes had to pause filming until the evening traffic noise subsided.

Rows of sound stages loomed nearby, and more than a few establishing shots accidentally revealed modern studio buildings that clearly didn’t belong on a deserted island.

The decision to film mostly in Southern California wasn’t unusual — television production was centered there — but it created the funny disconnect that the idyllic castaway paradise was actually surrounded by familiar Hollywood infrastructure.

Inside the studio, scenes such as hut interiors and the Professor’s inventive lab were shot on sound stages where lighting, sets, and props could be controlled.

Outside, the lagoon offered limited depth and visual scope, so directors had to use tight camera angles and careful editing to maintain the illusion of isolation.

Yet even with these limitations, the show’s history intersects with some remarkable real‑world events.

The pilot’s final day of filming, for example, was Friday, November 22, 1963 — the same day the nation reeled from the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

The cast and crew learned of the tragedy as they worked, listening to radio bulletins between takes.

That moment of national mourning is subtly captured in the show’s first season opening sequence: as the Minnow departs from Honolulu Harbor, an American flag flies at half‑staff in the background — a quiet testament to the era’s emotional weight.

The show’s creator, Sherwood Schwartz, also injected some quiet satire into the series. The ill‑fated boat was named the S.S. Minnow after Newton Minow, then‑chairman of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission.

Minow had famously criticized television programming as a “vast wasteland” during a 1961 speech, and Schwartz’s tongue‑in‑cheek choice was both an inside joke and a subtle commentary on the state of television entertainment — including the type of whimsical, implausible series his show represented.

Behind the scenes, the cast itself became a close‑knit ensemble that helped the show thrive despite its limitations.

Alan Hale Jr., who played the loyal and steady Skipper, went to considerable lengths to audition for the part, determined to land a role that he felt matched his own adventurous spirit.

Bob Denver, the bumbling and beloved Gilligan, was passionate about his co‑stars receiving recognition; he successfully lobbied for all seven main actors to be named in the show’s theme song lyrics, ensuring none were overshadowed in the iconic opening sequence.

The actors brought their own personalities and humor to the set, contributing to off‑screen bonds that mirrored the on‑screen camaraderie of their characters.

Stories from cast and crew members recount laughter, improvisation, and genuine friendship during breaks in filming.

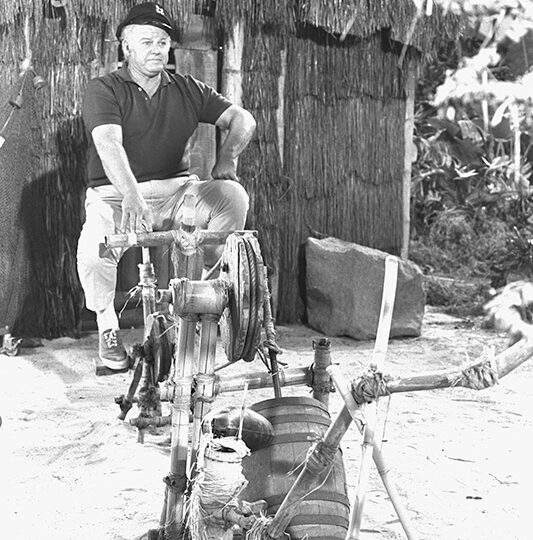

Some of these anecdotes have become almost as beloved as the episodes themselves, with fans poring over behind‑the‑scenes photos and interviews to catch glimpses of unguarded moments on set.

Over the decades, Gilligan’s Island also became a source of inspiration for fan theories, parody, and affectionate cultural reference.

Viewers have often joked about how the castaways never seemed to run out of clean clothes, makeup, or fresh food despite their supposed plight, or why they never simply repurposed more of the island’s driftwood into a rescue raft.

These questions became part of the show’s mythology, spawning discussions, memes, fan fiction, and nostalgic retrospectives that celebrate both its strengths and its delightful absurdities.

Even the show’s place in television history reflects its influence.

Although it only ran for 98 episodes across three seasons, Gilligan’s Island entered syndication — where it arguably became far more widely known than during its original broadcast.

Daytime and late‑night reruns in the 1970s, 1980s, and beyond introduced the castaways to new audiences, many of whom embraced the series for its humor, its colorful characters, and its unpretentious storytelling.

The show’s tropes — like the bumbling hero, the eccentric millionaire, and the brainy schemer — became archetypes that echoed in later sitcoms and cartoons.

In the years since the original series, new installments such as television movies and reunions have revisited the island and its inhabitants, blending nostalgia with new twists.

Even though some actors passed away or were replaced due to health issues, the affection for the characters and their island misadventures remained strong.

Fans continued to celebrate the series through memorabilia, conventions, fan clubs, and online communities dedicated to every nuance of the show — including goofs, trivia, and rarely seen production photos.

Today, with Tina Louise — who played Ginger Grant — as the last surviving original cast member, Gilligan’s Island stands as a remarkable example of how an imperfect production can become timeless.

Its enduring appeal isn’t just about tropical sunsets and slapstick misunderstandings; it’s about the human moments of warmth between the castaways, the lovable naivete of Gilligan, the Skipper’s protective gruffness, and the way each character’s quirks contributed to a sense of family on screen.

The series’ bloopers, continuity quirks, and behind‑the‑camera stories have only deepened the affection audiences feel for this beloved classic.

In the end, Gilligan’s Island reminds us that television doesn’t have to be perfect to be treasured.

It only needs heart, humor, and enough personality to make viewers care — and that’s exactly what generations have found in this sun‑soaked sitcom, one “three‑hour tour” at a time.